- She was lonely at the top, stays lonely at the bottom

Harinder Baweja

Driving through the picturesque countryside in South Kashmir, where she was campaigning for the 2014 assembly elections, Mehbooba Mufti was clear about one thing. “There is no question of allying with the BJP. We have nothing in common,’’ she told me as she hopped in and out of the car. Each time she got out, she made sure to wear shades.” Why do you wear dark glasses,” I asked, wondering why she would not want eye contact with her constituents. “The people throw toffees and I’ve escaped being hurt,” I remember her saying.

The toffees soon turned to stones. The leader went from rally to rally, asking voters to come out and vote in larger numbers, because it was important to ensure “that the BJP does not open its account in the Valley.” Yet, once the results were announced, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) was in coalition talks with the very party it had sought to keep out of Kashmir.

The once-gutsy woman politician, always quick to be with the families of those who lost their loved ones, must be given credit for creating the party from scratch. She had the political instinct to steer the party to electoral victory on more than one occasion, but her instinct failed her when it came to sharing power with the BJP.

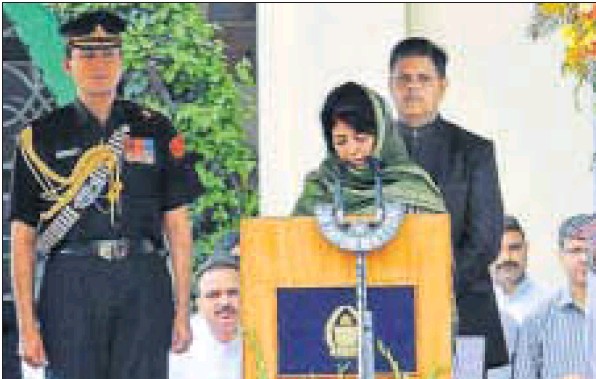

She had the chance to repair the damage after her father, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, died while in office, but she took centre stage, to be sworn in as the first woman chief minister of the state. The feisty street fighter swiftly moved from being a soft separatist to being what many in Kashmir called an ultranationalist.

Mehbooba, who earned her political spurs advocating a withdrawal of the draconian armed forces special powers act and a soft border with Pakistan, soon saw her traditional stronghold of south Kashmir slip from under her feet. The first testimony came in the form of an extremely low turnout for her father’s burial.

South Kashmir is now the new hotbed of militancy, the seismic zone that militant commander Burhan Wani operated out of; the area from where a maximum number of youth disappear into the mountains surrounding it, only to reappear on social media, gun in hand.

The once-grounded politician had so completely withdrawn into a shell, after pellet wounds became the new leitmotif, she did not even heed political advice from within the party to consider walking out of the alliance with the BJP. When asked last year, by an aide why she didn’t resign, she looked surprised, the aide said.

She realised perhaps that it was already too late. Neither she nor her elected legislators were able to visit their constituencies, without the fear of an attack or a run-in with angry youth stone pelters. On each foray I made into South Kashmir after Wani’s killing in 2016, I faced angry questions: “Where is Mehbooba? Send her here. We want to ask her why she asked for our vote and then embraced the BJP.”

The ‘ultranationalist’ braved insults and humiliation at the hands of her alliance partner who contradicted and questioned her on every move. She was berated for calling for a dialogue with the separatists and with Pakistan and the only time she had her way was after the outrage over the Kathua child rape-murder. That was the one time she secured the resignations of two BJP ministers who had taken part in a rally in defence of suspects in the crime.

In the end, her allies beat her in the political game. The BJP pulled the plug on the alliance when she least expected it. They made a political move in the hope of salvaging themselves in Jammu from where they won 25 seats. Mehbooba has emerged as the biggest political loser. She was lonely at the top and stays lonely at the bottom.

Courtesy: Hindustan Times: 20 Jun 2018